|

British

Columbia Passenger License Plates

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Quick Links: |

The period between 1931 and 1976 is considered to be the "Prison Era" when BC plates were manufactured by inmates at Oakalla Prison in Burnaby. |

* * * * * |

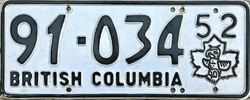

The Totem! A polarizing license plate in its day and ultimately an ill-fated one, but also one of the most visually striking designs the province ever issued (as well as a favourite amongst collectors), it represents the confluence of a number of different forces buffeting public policy debates in British Columbia at this time; from resource and northern development, to tourism promotion, the creeping dominance of car culture and, finally, early contestations over identity. |

| The Totem | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

While British Columbia had attempted to use renewable license plates between 1918 and 1922, these had been abandoned due to concerns around theft and identification. Despite the technology have not advanced much in the proceeding 30 years - metal tabs and windshield stickers remained the common options - the rationing of the War Years had underscored the wasteful demands of annual license plate production. In response, jurisdictions across North America were exploring the idea of “permanent” license plate with renewed interest by the late 1940s.

On March 18, 1950, Attorney-General, Gordon Wismer, unveiled a suite of legislative changes to the Motor Vehicle Act based on the recommendations of Kellogg and Stevenson to streamline the operation of the MVB. One of the major changes announced was the introduction of five-year license plates that would be renewed through the use of metal tabs. Due to production timelines, the five-year plates would not be ready until 1952 as renewal strips were already being manufactured in Oakalla for use in 1951. George Hood, Superintendent of the MVB did announce that a “heavy-duty” license plate would be made for issuance in 1952 capable of withstanding five years of use ... |

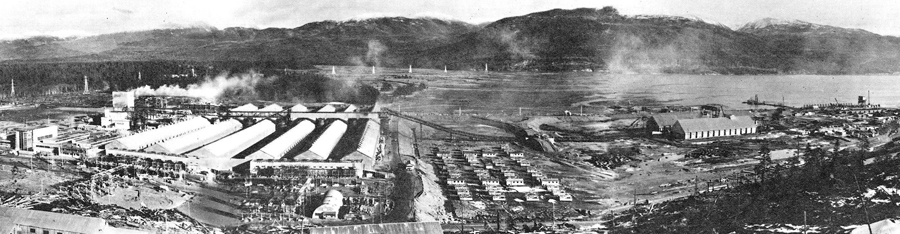

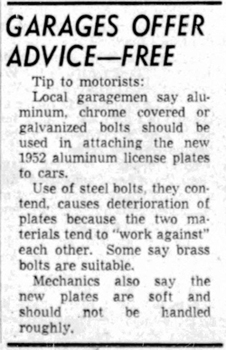

The challenges presented by the use of aluminum for license plates in this era would have been known to the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) as the material experienced a bit of a fad in the immediate post-war period, with issuing authorities across the U.S. and even in some Canadian provinces experimenting with it. Connecticut had kicked started the trend in 1937 when it became the first state to use an unfinished aluminum base, which also happened to become the first successful multi-year “permanent” license plate (used for 19 straight years). In Canada, Alberta would issue the first unfinished aluminum plate in 1939, but the use of aluminum would not really take off until after the end of the Second World War.

This, according to Bill Johnson (Early New Mexico License Plates), was a result of the transition from a wartime economy and a surplus of tens of thousands of unneeded military aircraft - either finished or still under production - in factories across the US. The vast majority of these planes would be scrapped, making available a significant amount of aluminum at very competitive prices. The following gallery is an example of this: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The use of aluminum was, however, presenting a number of challenges, the most notable of which was its durability (as noted above by the Port Moody trucking company), as the plates were prone to fatigue cracks caused by road induced vibration which ultimately resulted in them becoming damaged and potentially falling off vehicles. This prompted a number of states to abandon the use of aluminum in the late 1940s after only a single year. A number of other states, however, tried to improve the durability of Aluminum plates in the late-1940s by experimenting with a “waffle” design which used a hatch-textured base to add strength to the plate: |

|

|

|

|

Alcan Smelter at Kitimat (circa 1954) |

Further influencing the design of the 1952 license plate was the revelation in 1950 that, for the first time, Canadian tourists had spent more in the United States than had American tourists coming to Canada. In May of that year, the American Consul General in Vancouver, Alfred Klieforth, had given a speech to the Vancouver Junior Chamber of Commerce in which he suggested that Americans travel to Canada in order to “find different things from those seen at home” and that “some organization should seize on the colorful traditions of the people of different nationalities in Vancouver and develop them.” Klieforth then mentioned license plates as the ideal way to “increase the tourist trade” through the use of a unique symbol or slogan.

To this end, the “Totem-Land Society” was formed in July of 1950 and included a “who's who” of the Vancouver political and business elite. Honourary positions were granted to the Premier (Byron Johnson), Attorney-General (Gordon Wismer), Minister of Trade and Industry (Leslie Eyres), and President of the BC Native Brotherhood (Chief William Scow). Active positions included the Mayor of Vancouver (Charles Thompson), President of the PNE (H.M. King), President of the Vancouver Board of Trade (William Swan), President of the BCAA (Peard Sutherland), and so on ...

While the inclusion of a totem slogan and emblem was reported to be a “long standing dream” of the group's honourary solicitor R. Rowe Holland, it was the Society's Secretary, Harry Duker who was the “power behind [the] movement to popularize [the] totem pole as [a] tourist attraction.” Duker's job of getting the emblem on license plates was certainly aided by the presence in the Society of Wismer, who was responsible for the MVB as Attorney-General, and Eyres. Both men were also reported to have endorsed the idea of a totem emblem.

A mere one-month later, the Society appeared to have achieved its objective when Superintendent Hood (who reported to Wismer) announced that “the new semi-permanent license plates, to be issued in 1952, will carry the Thunderbird figure as emblematic of B.C.” (NOTE: the inclusion of an emblem on a license plate was labeled by the press as going “American”)

In rejecting the inclusion of the “Totem Land” slogan, Hood provided a somewhat implausible excuse of the dies for the new plates having already been settled upon and it was too late to adjust these for the slogan (but not the dies?). More likely was that there simply was not enough space on the new plates to accommodate the date, serial number, jurisdiction and, now, the inclusion of an emblem.

The Vancouver Province newspaper quickly printed an editorial expressing its disappointment. After many years of asking the provincial government to put some form of emblem on license plates the newspaper had hoped that the emblem would “be more than the black maple leaf now proposed ... [and that] a colorful B.C. totem pole would be a better highway ambassador when our cars on traveling in far places.” While it is not known what had served as the inspiration for placing the Maple Leaf on the plates, the notion that provincial license plates should indicate “CANADA” in order to help orient Americans as to where the driver resided had been floating around for years.

This emblem, likely the result of bureaucratic decision-making by committee, had the result of detracting from both the Maple Leaf and the Thunderbird as they each became lost within the other. The design was criticized almost immediately after its unveiling. The Province newspaper acknowledged the shortcomings of the design and editorialised that “the totem pole should look like a totem pole” while the Victoria Daily Colonist questioned the relevance of totem poles to contemporary British Columbia (“How many genuine Indian carvings are left . . . to see?”) and the merits of the design (“It isn’t simple enough to be really striking”). The Totem-Land Society was even less forgiving, proclaiming “it doesn’t look like anything. The totem is not even a copy of an original and is practically obliterated on the maple leaf background. All that was needed was a bright totem pole and the word “Totem-Land” or better still, “Land of the Totem” . . . we are making a mess of a colourful and interesting publicity idea for B.C.” It also soon came to light that the Totem emblem had been copyrighted to the Vancouver Board of Trade and its use by businesses, groups or individuals in promotional or advertising material required the submission of a $35 application ($415 in 2023 dollars) to the Board of Trade for its consideration.

To obscure the emblem raised the risk of citation by the police for defacing the license plates, while the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) did not offer any alternative options for drivers who objected to the design. |

|||||

Frank Calder (shown at right) had been elected to the Legislature in 1949 as the Member for Atlin as part of the (then) Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) Party.

The topic that Calder had chosen to speak on was license plates(!) and was summarised by the press as follows:

Calder went on to serve over 20 years in the Legislature for three different political parties (CCF, NDP and Social Credit) and is most famous for the 1973 Supreme Court of Canada decision that bears his name (Calder v British Columbia) and established that Aboriginal title exists in modern Canadian law. To read more about Frank Calder, Click here! |

The solution that the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) came up with, the use of letters and numbers as had occurred between 1941 and 1948, while not novel, was poorly executed. Whereas the use of letters in the 1940s made some intuitive sense, being issued alphabetically and always in the same location on the plates, the use of letters on the Totem plates appeared random and ad hoc and did not always lend themselves to quick memorization by the public or law enforcement. That said, with the benefit of access to the Distribution List used by the MVB some semblance of order can be discerned in the use of letters on the Totems. One of the easiest way to understand how these plates were issued is to think of it as being three (3) distinct blocs of between 50,000 to 100,000 plates that were provided to different parts of the province based upon a certain urban hierarchy. What can be considered as the first bloc of 100,000 plates were the traditional all-numeric plates displaying the “00-000” format. These were issued to the majority of MVB offices across the province, most of which were in the smaller urban/rural areas - with the exception of Victoria which retained it status as the location from which the first bloc of plates (and, most importantly, No. 1) were issued: |

| 1st Bloc - "00-000" format | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

ALBERNI: 40-001 TO 43-700 |

ASHCROFT

43,701 TO 44,050 |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

BARKERVILLE 44-101 TO 44-250 |

BURNS LAKE 44-251 TO 45-150 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CLINTON 45-151 TO 45-400 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

DUNCAN: 53-201 TO 57-500 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

FIELD 59-551 TO 59-650 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

GREENWOOD 60-351 TO 60-700 |

KASLO 60-701 TO 60-950 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

LILLOOET 65-951 TO 66-350 |

BRALORNE 66-351 TO 66-650 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NANAIMO: 67-151 TO 73-650 |

NEW DENVER 73-651 TO 74-000 |

NAKUSP 74-001 TO 74-200 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

POWELL RIVER: 82-101 TO 83-700 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

PRINCETON 88-101 TO 89-300 |

QUESNEL 89-301 TO 90-300 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

SALMON ARM 91-951 TO 93-550 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ENDERBY 99-001 TO 99-350 |

WILLIAMS LAKE 99-351 TO 99-999 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The second bloc of approximately 83,992 plates displayed a single letter prefix - i.e. "A0-000" - and were issued exclusively to the City of Vancouver, which was and remains the largest city in the Province. |

| 2nd Bloc - "A0-000" format | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The third bloc of approximately 50,051 plates incorporated a single letter as the second character - i.e. "0A-000" - and were issued to eleven mid level urban areas or regional centres of the province such as New Westminster and Kamloops, etc ... |

| 3rd Bloc - "0A-000" format | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

First plate issued in New Westminster - 1A-1. |

A number of single letter prefix plates were retained at the Victoria Stock Room for issuance later in the year to other offices on an as-needs basis. While available records only make reference to the "T" and "U" prefixes, the presence of "W" & "Y" prefixes signifies that additional plates were required prior to the end of the 1952 issuing year. |

| 1952 Over-run | |||||||||||||||||

|

For those familiar with our National Parks page, red borders on a plate were used to allow local residents free access to Banff, Yoho and Kootenay National Parks. Unfortunately, as this series of "T" plates is over-run, we don't know if it was issued in Field or Golden and if the red borders are related to the Parks. Nevertheless ... |

As can happen on occassion, over-run plates produced later in series will display variations not seen on earlier plates. This is evident with the "W" & "Y" prefix plates, which were produced after the initial over-run plates in the "T" & "U" blocks had been issued. For whatever reason, the dash between the "W" and serial numbers appears to have been dropped when the "W" block moved to 5-characters (i.e. possibly around the transition from "W-999" to "W1-000") while the totem logo and "52" date stamps appear to have been dropped around the transition from plate No. "W9999" to "W5000": |

"W" Series Variations |

||||

|

2-digit

|

|

||

|

||||

Although available examples of the "Y" prefix plates are limited, it appears that this block was more consistent in terms of its use of the dash, which was restored, and the totem logo and "52" date stamp, both of which discarded from the plates: |

"Y" Series |

||

1-digit

|

2-digit

|

|

|

||

In attempting to explain this new system to motorists, the press explained how Victoria and Vancouver would be given plates displaying A, E, H, J, K, P, R, S, T and U, but that:

The writer concluded by asking; “Confusing, isn't it?”

More on this below ... |

|

.jpg) |

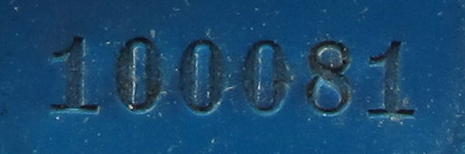

It is always important to look at these serials as you might have a low number, such as the tab shown at left, which is the 81st issued. |

Information regarding the distribution of tabs and which numbers were issued from which particular Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) can be found on our Registration Data page: Click here! |

Police reminded motorists the same thing had happened in 1951 (and, as we know, in 1919, 1921 & 1922 as well) and that “the crooks won't take the time to remove them if they have been bolted on and the end of the bolts cinched over but if they see a set tied on with string - well, it's easier than paying for them.” The cost to replace a lost or stolen tab was $2.00.

In one amusing story shortly after these warnings, an irate citizen stormed into the MVB office to complain that one of the two 1953 tabs he had bought the day before had already been stolen. A patient official accompanied the complainant outside, took a look at the car, and gently pointed out that both plates were firmly bolted together on the rear bracket. Directors of the British Columbia Automobile Association (BCAA) soon passed a resolution calling ont he provincial government to “look for a more suitable type of license plate than the present 1953 tabs ... [as[ the tabs can be stolen too easily”.

The reason given was the difficulty of trying to match the renewal tab affixed to a license plate as being the proper one that was issued by the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) for that vehicle. Compounding matters was the revelation that “there is no record kept of serial numbers of tabs to motorists ... [allowing] an unscrupulous individual to steal a tab from a car, place it on his own vehicle and make it difficult to prove a crime ... Also, tiny numbers on the tabs can't seen without closeup inspection.” While it was reported that Commercial vehicles would return to an annual license plate (sans tabs) in 1954, this was not going to be possible for passenger vehicles as the 1954 tabs were already being made at the Oakalla Plate Shop.

The Attorney-General, Robert Bonner, was quoted as saying “by returning to steel plates and abandoning the tab system we can give the motorist better service at less cost.”

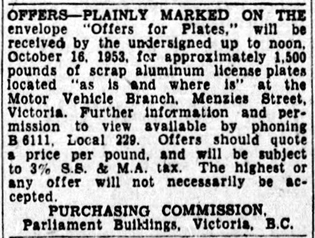

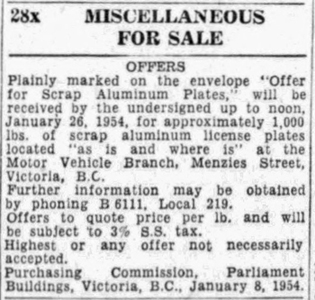

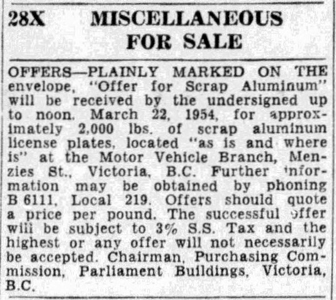

Much like British Columbia, the Alberta plates suffered from a theft-friendly tab with miniscule identification numbers that made confirming the tab matched the base plate almost impossible. Two months later, the first in a series of classified ads appears in the Victoria press notifying anyone who might have a need for scrap aluminum that the MVB had approximately 4,500 pounds to dispose of located “as is and where is” at its Menzies Street office: |

|

|

|

| Various classified ads that appeared between October of 1953 and March of 1954 for approximately 4,500 pounds of scrap aluminum license plates. |

Apparently, the use of letters, at least the way they were utilised on the Totem base, was found “to complicate filing systems, and law officers find identification difficult under some circumstances.” The provincial election of June 1952 had also brought to power the Social Credit Party under W.A.C. Bennett, which had little representation in the Vancouver area or from the Vancouver business community and likely felt little allegiance to the Totem design. Predictably, the Vancouver business community, supported by the editorial pages of the major daily newspapers rolled into action at this news. The Victoria Times wondered why a slogan such as “The Land of Parks” or something similar could not be used to “draw attention to the attraction of this part of Canada to the tourist?” In March of 1954, Harry Duker traveled to Victoria in order to lobby the provincial government in the hope that it would retain some form of Totem branding on the 1955 license plates, which were to be manufactured beginning the following month.

Duker's proposed compromise was the inclusion of a “Totemland” slogan to be placed along the top of the new plates. In a blast from the past, the Victoria Junior Chamber of Commerce (JCC) revived its work from the late 1920s and called for a license plate design that included an insignia promoting the province such as “Sportsman's Paradise” or “Home of the Totem.” Regarding the current Totem design, the declared it to “indecipherable and unintelligible”. (January 1953). Working against Duker and the JCC was a broader initiative to standardize license plate design across North America in order to facilitate car design and the specifications needed for mounting the plates. This was going to result in a mandatory 6 inch x 12 inch plate size, which was 2 inches shorter than the 1952 base and left little space for a stamped emblem. To read more about this standardization of plates, see the next page; 1955-63.

The Victoria Colonist headlined an article “Totemland Slogan Scored as Fraud Against Tourists” on the basis that “whatever it may have been in the past, B.C. certainly is not a totemland today” and inducing tourists to come to the province to see something that doesn't exist was simply misleading advertising. On April 26, 1954, the government officially nixed the inclusion of any slogan on the 1955 license plates, including “Totemland”, “Industry Moves West” and “Land of Beauty”. In a celebratory mood, E.A. Simmons wrote a letter to the Editors of both the Sun and Province newspapers commending the provincial government for “its wisdom” in rejecting the “Totemland” slogan. He further suggested that;

A minor dissent was registered by the Canadian Daughters' League (CDL) who objected to the removal of the Maple Leaf emblem from the license plates. |

As can be seen in the issuing statistics for the 3rd bloc of plates, not all letters were initially manufactured, with only 4,000 sets of plates where the second character was an 'S' being issued to the Kootenay communities of Nelson, Salmo and Castlegar. The Branch subsequently produced plates with these remaining combinations in order to meet demand and, based upon the absence of the "Totem" or a year, it is estimated that these were issued sometime between 1953 & 1954. |

| Additional Over-run | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1954 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

Although the MVB had retained approximately 15,000 plates for future use in the Stock Room in Victoria as part of the 1952 issuance, this proved insufficient to meet the need for new registrations throughout 1953 and 1954 and a new series of approximately 60,000 plates incorporating a single-letter suffix (i.e. 0-000A) were manufactured. Unfortunately, the available MVB records for 1953 and 1954 only provide details on the serial numbers that appeared on the renewal tabs and not the number of additional plates that were manufactured to accommodate the need for new license plates. Nevertheless, it is possible to identify these plates through the absence of the Totem emblem on the base plate - which has been left blank. |

1953

- 1954 Base Plates |

||

| Interestingly, the letter "D" has now made an appearance, with the series ending in the "K" range. If you have a plate with a letter combination not shown here, it is also possible that you might be looking at Commercial (C), Farm (F) or Dealer (D) plate. |

As BC was scrapping its latest attempt at permanent license plates, Missouri was pioneering a solution to the problem of an efficient renewal system that also combatted theft; the use of plastic registration decals to be stuck directly to a licence plate: |

||

|

||

Missouri would be followed by California - a state to which British Columbia would often look for inspiration - Nevada, Arizona, Pennsylvania and Washington by 1959. In Canada, the Maritime provinces of New Brunswick and PEI would be the first to use decals. To read more about these innovations, see our page on Decals by; Clicking Here! |

Quick Links: |

Antique | APEC | BC Parks | Chauffeur Badges | Collector | Commercial Truck | Consul | Dealer | Decals | Driver's Licences | Farm | Ham Radio | Industrial Vehicle | Keytags | Lieutenant Governor | Logging | Manufacturer | Medical Doctor | Memorial Cross | Motive Fuel | Motor Carrier | Motorcycle | Movie Props | Municipal | National Defence | Off-Road Vehicle | Olympics | Passenger | Personalized | Prorated | Prototype | Public Works | Reciprocity | Repairer | Restricted | Sample | Special Agreement | Temporary Permits | Trailer | Transporter | Veteran | Miscellaneous |

© Copyright Christopher John Garrish. All rights reserved.

In British Columbia, this took the form of the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) commissioning an efficiency study by the firm of Kellogg and Stevenson (“efficiency experts”) to make recommendation on a “permanent” license plate.

In British Columbia, this took the form of the Motor Vehicle Branch (MVB) commissioning an efficiency study by the firm of Kellogg and Stevenson (“efficiency experts”) to make recommendation on a “permanent” license plate.

For anyone who has ever held a 1950 British Columbia license plate that has been made out of steel versus the Totem license plate made of aluminum, it is readily evident that the province did not, in fact, produce a “heavy-duty” license plate in 1952 that would be capable of

withstanding five continuous years of use.

For anyone who has ever held a 1950 British Columbia license plate that has been made out of steel versus the Totem license plate made of aluminum, it is readily evident that the province did not, in fact, produce a “heavy-duty” license plate in 1952 that would be capable of

withstanding five continuous years of use. “B.C.'s five-year aluminum license plates won't even last one year” was the prediction made by a Port Moody trucking company after it was fined for not displaying a front license plate in October of 1952. This was because the plates were proving flimsy and unable to withstand the normal vibrations and wear-and-tear associated with the operation of a truck.

“B.C.'s five-year aluminum license plates won't even last one year” was the prediction made by a Port Moody trucking company after it was fined for not displaying a front license plate in October of 1952. This was because the plates were proving flimsy and unable to withstand the normal vibrations and wear-and-tear associated with the operation of a truck.

Taking their cue, local business leaders determined that British Columbia needed differentiate itself from the rest of the continent as a tourist destination and that the best way to do this was through the commodification of West Coast Native art culture - namely the totem pole.

Taking their cue, local business leaders determined that British Columbia needed differentiate itself from the rest of the continent as a tourist destination and that the best way to do this was through the commodification of West Coast Native art culture - namely the totem pole. In announcing the group, Mayor Thompson declared its purpose was to help

In announcing the group, Mayor Thompson declared its purpose was to help

Like clockwork, the Vancouver Province newspaper chimes in with an editorial a few days later praising these “publicly-spirited men” and extolling the virtues of a totem pole on BC license plates (“free advertising”!).

Like clockwork, the Vancouver Province newspaper chimes in with an editorial a few days later praising these “publicly-spirited men” and extolling the virtues of a totem pole on BC license plates (“free advertising”!).

What changed between August of 1950 and March of 1951 is unknown, but when Members of the Legislature were provided with a sneak peak of the 1952 license plates, the Totem had been replaced with an outline of a Maple Leaf!

What changed between August of 1950 and March of 1951 is unknown, but when Members of the Legislature were provided with a sneak peak of the 1952 license plates, the Totem had been replaced with an outline of a Maple Leaf! What happened next is unknown and probably lost to time, but two months later (May of 1951) it was being reported that “some thousands of the 1952 plates have already been made”, and by September of 1951 it was formally confirmed that the design of these plates had been changed to include a totem pole ... inside the maple leaf emblem!

What happened next is unknown and probably lost to time, but two months later (May of 1951) it was being reported that “some thousands of the 1952 plates have already been made”, and by September of 1951 it was formally confirmed that the design of these plates had been changed to include a totem pole ... inside the maple leaf emblem! This raised the hackles of many motorists who, in an era when the use of license plates for promotional purposes (whether civic or otherwise) was still contested ground, objected to having their cars turned into mobile billboards for the Vancouver Board of Trade.

This raised the hackles of many motorists who, in an era when the use of license plates for promotional purposes (whether civic or otherwise) was still contested ground, objected to having their cars turned into mobile billboards for the Vancouver Board of Trade.  On March 14, 1952 - two weeks into the new vehicle registration year - the major Vancouver newspapers reported that “for the first time in Canadian parliamentary history, an Indian legislator has delivered an address in his native tongue from the floor of a provincial legislature.”

On March 14, 1952 - two weeks into the new vehicle registration year - the major Vancouver newspapers reported that “for the first time in Canadian parliamentary history, an Indian legislator has delivered an address in his native tongue from the floor of a provincial legislature.” After speaking for what was reported to be three minutes in “Nishga” (now spelled Nishga'a), Calder repeated his comments in English “for the benefit of those who are new in my country.”

After speaking for what was reported to be three minutes in “Nishga” (now spelled Nishga'a), Calder repeated his comments in English “for the benefit of those who are new in my country.”  While the use of the Totem was clearly pursued in support of an economic agenda and not a desire for meaningful reconciliation, its use nevertheless engendered “a perceived sense of threat” amongst some.

While the use of the Totem was clearly pursued in support of an economic agenda and not a desire for meaningful reconciliation, its use nevertheless engendered “a perceived sense of threat” amongst some.  In Victoria, David Brock was writing in the Daily Times that the Totem is “evidence ... [of] the Motor-Vehicles Branch [compelling] you, whether you like it or not, to drive round advertising your fake eagle-ism. If you refuse to turn your car into a billboard ... of the Eagle clan, then it becomes illegal for you to drive. Which is not only tyranny, but a very nasty pun, what with ill eagle and illegal and all.”

In Victoria, David Brock was writing in the Daily Times that the Totem is “evidence ... [of] the Motor-Vehicles Branch [compelling] you, whether you like it or not, to drive round advertising your fake eagle-ism. If you refuse to turn your car into a billboard ... of the Eagle clan, then it becomes illegal for you to drive. Which is not only tyranny, but a very nasty pun, what with ill eagle and illegal and all.”

Few, however, were as put out by the design as E.A. Simmons, a local Funeral Director (shown at left), who proceeded to wage a one-man crusade against totem poles through the Letter to the Editor pages of the Vancouver Sun and Province.

Few, however, were as put out by the design as E.A. Simmons, a local Funeral Director (shown at left), who proceeded to wage a one-man crusade against totem poles through the Letter to the Editor pages of the Vancouver Sun and Province. A more mundane challenge associated with the Totem was administrative and accommodating the issuance of between 250,000 to 350,000 license plates over five years with space for only five characters (due to the space taken by the Totem).

A more mundane challenge associated with the Totem was administrative and accommodating the issuance of between 250,000 to 350,000 license plates over five years with space for only five characters (due to the space taken by the Totem).

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

In Vancouver, the travails of a MVB clerk learning the new system (a temporary hire for the end of year rush) made the local papers after mistakenly issuing Truck plates (“C” prefix) to passenger vehicle owners. An honest mistake, right?

In Vancouver, the travails of a MVB clerk learning the new system (a temporary hire for the end of year rush) made the local papers after mistakenly issuing Truck plates (“C” prefix) to passenger vehicle owners. An honest mistake, right?

In what would prove to be the downfall of the Totem base, within weeks of the 1953 renewal tabs being issued, police reported “a flurry of thefts” and were warning motorists to have the tabs firmly fastened to their license plates.

In what would prove to be the downfall of the Totem base, within weeks of the 1953 renewal tabs being issued, police reported “a flurry of thefts” and were warning motorists to have the tabs firmly fastened to their license plates.

Two weeks later, the provincial government hinted that it would be abandoning the tab renewal system and returning to the issuance of new license plates each year.

Two weeks later, the provincial government hinted that it would be abandoning the tab renewal system and returning to the issuance of new license plates each year. The formal announcement came in August of 1953 and reconfirmed everything that had been reported five months earlier; “the tabs provided inadequate identification, and the aluminum plates have not stood up.”

The formal announcement came in August of 1953 and reconfirmed everything that had been reported five months earlier; “the tabs provided inadequate identification, and the aluminum plates have not stood up.” Whether by design or coincidence, the Alberta Government announced the very next day that it too was abandoning its experiment with permanent license plates and returning to a system in which new plate would be issued each year.

Whether by design or coincidence, the Alberta Government announced the very next day that it too was abandoning its experiment with permanent license plates and returning to a system in which new plate would be issued each year. It was further announced that use of the Totem emblem as well as letters in the serial number was unlikely to be continued and that no decision had been made about the introduction of a slogan such as “Evergreen Playground” or “Dogwood Land”.

It was further announced that use of the Totem emblem as well as letters in the serial number was unlikely to be continued and that no decision had been made about the introduction of a slogan such as “Evergreen Playground” or “Dogwood Land”.

The usual suspects came out to oppose the continuance of the Totem emblem, including Harold Weir, who reminded his readers that he “would feel silly as all get-out in proclaiming to the world at large that I hailed from 'Totemland' ... When I have to carry that bit of foolery around on my car I'll taker to wearing ruffles on my underpants.”

The usual suspects came out to oppose the continuance of the Totem emblem, including Harold Weir, who reminded his readers that he “would feel silly as all get-out in proclaiming to the world at large that I hailed from 'Totemland' ... When I have to carry that bit of foolery around on my car I'll taker to wearing ruffles on my underpants.”